Helping Haiti

A personal essay about a trip to two small towns in remote Haiti where a group in my own community is working on substantial projects in educational and medical development. Along the way I explore, among other things, the challenges to recovery in Haiti and the complicated question of foreign visitors (myself included) coming to take on charitable works in a country struggling to rebuild.

Published June 2012

by Christopher Hebert

For a long time now, particularly since the 2010 earthquake that devastated Port-au-Prince and left as many as three hundred thousand dead, Haiti has existed in the imaginations of most outsiders as a land defined by tragedy, a place reduced to an accumulation of acute problems for which there seem to be few plausible solutions. We tend to focus—and not entirely without reason—on the seemingly intractable poverty, the social and economic inequality, the political instability, and the environmental degradation.

It’s in part because of some of these problems, and in part because of a personal attachment I feel for the country, that I’ve come here for the first time, on a nine-day trip in late December and early January 2012.

I arrive in Port-au-Prince on Thursday, December 29, 2011, one of ten members of group sent by the Haiti Outreach Program, an organization sponsored by the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Knoxville, Tennessee. In 1999, Sacred Heart was paired with the parish of St. Michel in Boucan-Carré in the Diocese of Hinche, a remote area in the Central Plateau region of Haiti. The material results of this partnership can be seen in a number of substantial projects in Boucan-Carré, including a hospital, a microfinance bank, a primary school, and now a high school. In an effort to expand their projects beyond Boucan-Carré, the Haiti Outreach Program is in the process of building a health clinic and a guest house in the even more remote mountain village of Bouli.

It is the projects in Bouli that bring us here now. We are an eclectic mix of Sacred Heart parishioners and clergy, students, and me, a non-parishioner and novelist. We will spend one day in Port-au-Prince, five days in Boucan-Carré, and three in Bouli.

Even two years after the quake, you don’t have to search long to find signs of the damage it wrought; you don’t even have to get off the plane. Although the Toussaint Louverture International Airport was only a minor casualty compared to many other structures in Port-au-Prince, it nevertheless lost its control tower and sustained damage to its international passenger terminal. Large parts of it are still under construction. The route through immigration and customs temporarily involves a detour by bus to a nearby warehouse.

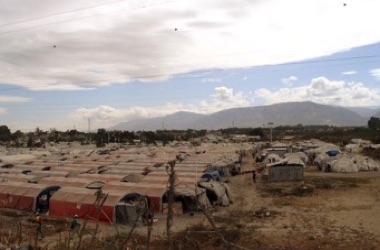

The destruction remains ubiquitous as we drive into the city. Just down the road from the airport is one of the several remaining encampments built for the million and a half people displaced by the earthquake. The camp is a dusty patchwork of muted blue tarps and muddy red tents. As we near the disaster’s second anniversary, more than half a million people still remain in settlements like these.

Gray dominates the landscape. The vibrant palate familiar to the tropics is here partly hidden beneath a cloudy film. Not just in the tent camps, but throughout the city: roads, buildings of bare cinderblock and cement, rubble. Even the trees in Port-au-Prince are a grayish green, their leaves coated in dust. It is the dry season, and the rubble and all the tearing down and rebuilding has turned the air chalky.

The damage is breathtaking, and I mean this not just metaphorically. Pedestrians on the crowded roadside routinely pass under hunks of concrete dangling like clusters of bananas. Lining the tightly packed roads are houses with foundations so badly damaged by the quake that the scrambled blocks look like untenable games of Jenga. It seems even a slight breeze could bring it all down.

I find myself holding my breath until we’ve passed.

And yet, untenable or not, people continue to live in such places; they have little choice. Housing is in short supply, and many of the people who initially sought shelter in camps ultimately decided they preferred to take their chances in their own ruined homes—even ones officially declared uninhabitable and marked for demolition.

For our first night in Haiti, the only one we’ll spend in Port-au-Prince, we’re staying at a guest house on Delmas 33, not far from the airport. Once we get settled in, we spend time together as a group, getting to know one another and going over our itinerary. There’s a large deck on the roof with a good view of the street below. It’s generally considered unsafe for foreigners to be out in Port-au-Prince at night, and we got here too late in the day to do any exploring. For now, we must content ourselves with what we can see and hear from this perch. Especially hear. There’s been a constant clamor since the moment we arrived. Music mostly, and not the distant strains of passing car stereos: loud, thumping, pounding beats that mortar us from all sides.

Most of the members of our group have never met until today. By way of introduction, we take turns talking about our personal reasons for being here. The majority of the others have come knowing little about Haiti. A lot of them have traveled extensively abroad and are drawn toward charitable works. They came to Haiti because that’s where Sacred Heart has focused its efforts. They want to do what they can to help.

When it’s my turn to talk, I fumble.

“I’ve spent the last eight years studying Haiti,” I say. “I’ve written a book loosely based on events here over the last several decades.”

Suddenly the noise all around us seems to melt away. I don’t know where to go from here. I realize I started at the end, rather than at the beginning. I’d like to try again, but how do I condense those eight years into something that makes sense?

Instead I try to explain that in the process of writing and researching the book, I’ve become attached to Haiti and to its people and culture and history. But that feels inadequate too. More than anything else, I realize, I’m here because I want to give something concrete back.

But in Haiti, even so simple an impulse as this become complicated. It’s estimated that there are more than three thousand non-governmental organizations working in Haiti. The country reportedly has the largest concentration of such groups, per capita, in the world, a distinction that has led to Haiti being known in the development community as “the Republic of NGOs.” Of late, more and more observers have been calling into question what these groups are actually accomplishing, and whether it’s appropriate for foreign organizations to play such an outsized role in shaping the affairs of a sovereign nation.

For individuals interested in philanthropic works, such debates often can’t help but feel pointlessly abstract. Why waste time debating when people are suffering and need help? And yet, for better or worse, these questions will remain with me throughout my stay.

§

At around ten o’clock, we call it a night; the music hasn’t stopped, but we have an early start in the morning.

As I’m getting into bed a few minutes later, I notice the music has suddenly gotten even louder. It’s mostly Haitian kompa, a modern electronic form of traditional meringue, a beat-heavy, up-tempo dance music. I put in my earplugs, and they shave off a decibel or two, not enough to make a difference. A pillow over my head does nothing at all.

As I lie here in the dark, trying to sleep, the din swells; singing and shouting weave into the mix. Every once in a while the music softens ever so slightly, and I’m able to nod off for a minute or two. But then someone cranks the volume back up again.

I keep expecting that at some point the music will have to stop. But it doesn’t. Hours and hours and hours pass.

Sleep is impossible. So instead I lie and I listen.

One consequence of thinking of Haiti as a republic of NGOs is that it encourages us to perceive of the place as merely a cause or a project or a laboratory for NGOs seeking to test the latest approaches to sustainable development. But the story of Haiti is more complicated than what we hear in the news. This has never been a country of passive victims. Despite its overwhelming problems, Haiti is still a place filled with real people living real lives.

Tonight, the story of these lives begins with the music. And the music doesn’t end until the room starts to brighten at the first light of dawn. That’s when the roosters take over. But after the music, the roosters are like a tranquilizer. I sleep for an hour, maybe two.

And then, at 6:30 in the morning, what finally wakes me up for good is a very different kind of sound: there is a rally going on somewhere in the city. There is a voice screaming into a bullhorn, and a crowd of people are shouting for justice.

§

For decades now, the name Haiti has been inseparable from the phrase “poorest country in the western hemisphere.” It’s a simplistic and patronizing epithet, but it’s nevertheless a fact worth remembering. How Haiti became so poor is a complicated story inextricably linked to its colonial past. The US, Haiti’s not-always-friendly neighbor to the north, has also played more than a small role in shaping the country’s fortunes.

Boucan-Carré is about sixty miles northeast of Port-au-Prince. The Central Plateau region, on the edge of which Boucan-Carré sits, is one of the poorest in this poorest of countries. Thanks to the new roads constructed by the United Nations, the drive here from Port-au-Prince, which used to take six hours, now takes only two and a half. The first hour and a half, along Route Nationale 3, winds smoothly, if slowly, into the mountains, past the city of Mirebalais. At Domond, the paved road ends and the bumps begin.

The rainy season is brutal to Haitian roads. The one to Boucan-Carré looks more like a dry stream bed than a thoroughfare. Even during the dry season, which we’re in now, the road requires strong suspension and an equally strong constitution. Father Duportal, the head of the St. Michel parish, picked us up this morning in Port-au-Prince. We are in his Land Cruiser, perhaps the only thing on four wheels able to handle such a road. Even in a tank like this, though, driving is delicate work.

In a country of warm, friendly people, Father Duportal is by a large measure the friendliest we’ve met, but even he is grimacing at the bumps. Every couple of yards we encounter gullies and ruts and boulders. It isn’t uncommon for us to have to come to a complete stop before we can figure out a way forward. With few exceptions, the only other vehicles are motorbikes.

The foot traffic along the road is constant, and many of the people navigating the rocks and pot holes are carrying enormous loads on their heads, everything from bananas to chairs. Donkeys bear the heavier burdens.

§

In March 2011, Boucan-Carré received electricity for the first time. Before then, the only available power was what came from the generators owned by the few people in the area able to afford them.

Most of the town’s nearly fifty thousand residents subsist on small-scale farming and charcoal production. Charcoal is the preferred method of cooking in Haiti, even where there is electricity. Its production requires the cutting down and burning of trees, and it’s one of the main reasons that Haiti is so badly deforested.

Boucan-Carré is where the Haiti Outreach Program has, to date, focused most of its efforts. The first medical mission arrived in 2000 with the goal of treating sick and malnourished school children, many of whom were unable to make the two- to three-hour trek required for them to get to class each day. HOP opened its first clinic in early 2001, enabling a nurse to continue this work on a permanent basis.

The lack of available health care has long been one of the biggest problems plaguing the Haitian countryside. Here, curable diseases often go untreated. In the absence of preventative measures, infectious diseases spread unabated. It’s not uncommon, in such a place, for diarrhea to be fatal. Childbirth is a gamble. Poor people in remote locations who wish to seek out emergency health care often must do so on the back of a donkey, traversing nearly impassable roads.

Paul Farmer’s Partners in Health has been at the forefront of efforts to provide effective, accessible health care in Haiti. In its earliest manifestation, PIH focused on HIV/AIDS in rural Haiti, but the last two decades have seen a vast expansion in the group’s mission, particularly at the Zanmi Lasante medical complex in Cange, not far from Boucan-Carré.

Soon after opening the Boucan-Carré clinic in 2001, the Haiti Outreach Program teamed up with Partners in Health, sharing expenses for staff, supplies, and various medical programs. Then, in 2004, they moved the clinic to a new location, adding a lab, radiology equipment, and an operating room. PIH also maintains AIDS and cholera clinics there. Adjacent to the hospital, and built the same year, is the Fonkoze microfinance bank, which provides small loans and financial services to the poorest of the poor.

In 2005, having made great strides in improving student health, HOP moved on to tackling the dilapidated school facilities in Boucan-Carré. The first project, undertaken with church partners in Missouri and Virginia, was expanding the town’s existing single-story primary school with a two-floor addition. The school now serves fifteen hundred students from as far as four miles away.

Just down the road from the primary school is the high school, currently under construction. This collaboration between HOP and several corporate and church sponsors is set to be finished in time for the start of the school year next fall. The high school has room for six hundred students. Around three hundred of them are now housed at several temporary locations in town, including the chapel and a derelict concrete structure adjacent to the church rectory. Once it’s no longer needed as a temporary school, that building will be torn down to its foundation. HOP has already drawn up blueprints for converting the space into a two-story building that will contain a restaurant and a cyber café on the first floor and guest quarters on the second—the only accommodations in a town that is becoming a hub for NGOs. The hope is that these businesses will be focal points around which to build a stronger local economy.

As I look around, peering into classrooms and examining future building sites, I can’t help feeling as though these efforts really are adding up to something meaningful, that at least in this small town, help is making a difference.

§

As in Port-au-Prince, the roosters and dogs wake us early the next morning. I’m up a little before six, grateful for what little sleep I manage to get.

While we’re eating breakfast, a twenty-one-year-old high school student stops by for a visit. He’s a familiar face for visitors from the Haiti Outreach Program, a bright, ambitious kid with excellent English, which he says he taught himself using books and CDs. He tell us he’s about to finish high school and that he’s hoping to go to college to study engineering. He adds, somewhat hopefully, that he’d like a scholarship to study abroad. I get the impression that he makes these visits when HOP groups are in town partly out of the hope that someday one of us might be able to make that happen. For this he can hardly be blamed. Foreign scholarships are rare and extremely competitive. Given the challenges he’s up against, initiative is one of his only options. Although there are engineering schools in Port-au-Prince, he says he doesn’t want to have to go there. It’s too dangerous, he says. “People are always getting shot.”

But while he wants to go abroad for his degree, he says he’d like to return to Haiti to work on building projects here. It’s long been one of Haiti’s greatest obstacles to solving social problems, that its most talented professionals often opt for the safety, stability, and far greater opportunity that they can find overseas.

A few hours later, as we’re driving from the construction site of the new high school in Boucan-Carré to the PIH-run tilapia hatchery down the road, Johnny, our translator, admits to me that he dislikes Port-au-Prince too. He prefers it here. “It’s more calm,” he says. “More quiet.”

Johnny is thirty-one and from Boucan-Carré. In addition to translating for visitors from HOP, he is overseeing the organization’s various building projects, including the high school in Boucan-Carré and the clinic and guesthouse in Bouli. Without Johnny, it’s hard to imagine how any of the HOP projects, not to mention its visits, would be possible.

Later in the afternoon, Johnny and Father Duportal drive us to Mirebalais to see the construction site of PIH’s massive new teaching hospital, one of the most exciting development projects underway in Haiti. At 180,000 square feet, the three-hundred-twenty-bed hospital will be one of the largest in the country. Perhaps more important than its size, however, is the role the facility will play in transforming the future of public health care in the country. In addition to delivering free services to patients, it will provide unprecedented opportunities for state-of-the-art training for young Haitian doctors and nurses. Its nine hundred Haitian workers will also make the hospital the single largest employer in the city.

The compound is vast and pristine, the outer walls so white they seem to glow. The hospital appears starkly out of place in the landscape, like an alien craft descended from the sky. But this is also why the project is so inspiring, creating a whole new sense of what is possible here.

Of course, Haiti is not lacking in examples of massive development projects that fail to realize their grand ambitions. But this is just as true of government- as non-government-sponsored projects. A case in point is Péligre Dam.

Following our visit to the hospital in Mirebalais, we drive about ten miles east on Route 3, following the Artibonite River upstream to where it meets a two hundred-thirty foot tall wall of concrete. The Péligre Dam is the largest on the island, which Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic. At sixty-one, Péligre Dam is now eleven years older than its intended lifespan. The attached hydroelectric plant, although still the source of most of Haiti’s electricity, is working at only partial capacity. Each year, its output decreases, as more and more silt from the eroding mountains clogs the turbines.

The dam was built in 1951 with the dream of encouraging large-scale agriculture, promoting tourism, and lighting up the entire country. None of those dreams came to pass. Aside from a couple of locals washing laundry on the shore, Lake Péligre—on the other side of the dam—is quiet and still. The beautiful view is the only tourist attraction, and the ten of us are the only tourists.

Although the promised development never materialized, several nightmares did, as we will see for ourselves in a several days. At long last, though, some of the plant’s power is reaching the poor as well as the rich.

But that power doesn’t always get to people in the way it’s intended to.

As we’re bouncing along the ruts and boulders back to Boucan-Carré after our tour of the dam, we approach two teenagers standing on either side of the road. One of them is holding a long forked stick in the air. The fork holds a wire, which runs across the street to a small block house. There are three of us in the front seat, and the realization seems to strike us at the exact same moment: the boys are attempting to splice into the live power lines running overhead. But by then it’s too late.

At the very moment we reach the two boys, the stick teeters. In what feels like slow motion, the wire falls, draping directly over the top of our Land Cruiser.

We skid to a stop. I grasp the dashboard, waiting for the jolt that will fry us in our skin.

By some miracle, the jolt never arrives. But even so, the unflappable Father Duportal finally loses his cool. He leans out the window, gesturing toward the power lines, shouting at the two boys that they could have killed us all.

The boys offer an apologetic wave.

As we drive away, they get back to work, reattaching the wire to the stick and raising it to the sky.

§

As the crow flies, Bouli is only several miles from Boucan-Carré. For the rest of us, it’s closer to twelve. But even that number is misleading. Along those twelve miles are several streams and rivers and (by my count) at least three substantial mountains.

We are lucky. We get to hitch a ride, at least for the first couple of miles to Sivol, the town where the road finally ends. That’s where we pick up our donkeys.

Although I would not have thought it possible, the stretch of road from Boucan-Carré to Sivol is even worse than the stretch from Domond to Boucan-Carré. Within just the first few minutes, we’ve splashed through three streams that during the rainy season doubtlessly become bona fide rivers. And then we come to a vast rocky bed as wide as a soccer field, and I feel as if we’re driving across a dry Mississippi. On the other side is an incline that leaves us almost vertical.

Our driver says a Land Cruiser will last only about five years on these roads. Nothing but a Land Cruiser (outfitted with a snorkel for the rainy season) can traverse them at all. It’s a luxury few Haitians can afford.

From Sivol, one gets to Bouli on foot. The only choice is between two feet and four. There are several eager takers for the donkeys; I’m willing to burden one with my sixty-pound backpack, but I prefer to walk.

This is not an easy place to be a donkey. In the absence of roads, donkeys bear the burden of everything that needs to be transported to and from Bouli. Food, textiles, building materials: all of it makes its way along a narrow mountain trail winding up to heights of around 2,300 feet.

Until you’re there, it can be hard to grasp just how vast and imposing the interior of Haiti truly is. Standing on a hillside outside of Sivol, we can see the literal truth behind the Haitian proverb, “deye mon, gen mon” (beyond the mountains are more mountains). The peaks and valleys stretch out to the horizon in every direction, and I’m reminded of that anecdote of the admiral who, asked by King George III to describe the island of Hispaniola, crumpled up a sheet of paper, saying “Sire, this is Hispaniola.” The Arawak Indians, the island’s original inhabitants, must have felt similarly; they were the first to call the place Ayiti—“land of the mountains.”

But while these vistas are breathtaking, they are also heartbreaking. The reason we can see every contour of this rough terrain is because there are virtually no trees—nothing to block the view, and nothing to obscure the edges of the countless slopes. Everything is plainly and precisely visible, including the incredible scope of the country’s deforestation. The entire landscape looks as though it’s covered with threadbare indoor/outdoor carpeting. It’s not uncommon to raise your eyes toward a distant mountaintop and spot a single tree standing out against the sky, like a flag planted on a barren moonscape.

The reasons for this deforestation are many and extend far back into the country’s history. They include the reliance on charcoal for cooking, as well as the exploitative harvesting and exporting of precious hardwood, the demands of rebuilding destroyed towns, and the clear-cutting that accompanies the expansion of farmland. Having lost its natural abundance of trees, the island is now losing its naturally fertile soil. Without roots to hold the land in place, it washes away with every rain.

We reach our destination in mid afternoon. Bouli is a town of a few thousand people nestled along a quiet river in a small, shaded valley. Houses are sparse, constructed of either wattle or stone and mud. There is no running water, no electricity. There are few structures here that aren’t private dwellings. For that reason, during the three days we spend here, we’ll be borrowing the house of the local sacristan.

§

There is no Home Depot in Bouli, Haiti. That fact is obvious, of course, but the significance of it is substantial. It means, for instance, that virtually every material for building must be found nearby. In such a remote place, even cinder blocks are out of the question; they’re too heavy for donkeys to carry in any significant number. So to build a wall you need rocks and cement. Rocks come from wherever you can find them: fields, paths, riverbeds. And the cement is not the pre-mixed kind; it requires sand, lots of it. To get the sand, you dig a hole and then you sift the dirt to remove the stones and gravel—a slow, laborious process. In addition to sand, making cement requires water. Since there’s no garden hose, every bucket must be carried up from the spring, which dribbles out of a pipe a hundred yards away.

It’s these complicated logistics that we’re puzzling through as we stand at the construction site of the guest house early the next morning. Before us is our task: the dirt floor. Beyond is the means with which we’re to finish it: sacks and sacks of cement.

We’re in the process of trying to assemble a viable plan for what we think we have to do when the Haitian crew arrives. Just in time, it turns out, to save us from mucking up the entire house and wasting most of the materials.

There are six guys on the crew, all in their twenties and thirties. They take little notice of us. The minute they get here, they set to work. They know exactly what needs to be done, and we—it immediately becomes clear—don’t have a clue.

We settle into our roles. The Haitian crew are the craftspeople. We are the common laborers. We tote water and cement, carry rocks, sift sand. Mostly we just try to be useful and not get in their way. All except for the young contractor in our group, whose feats of strength and endurance earn him the honorific Jom-Jom (which Johnny translates as “Strong-Strong”) from the Haitian crew. They are not easily impressed. With the exception of Jom-Jom, we cannot begin to keep up with them.

The guy mixing the concrete, using only a shovel, is especially tireless. He’s in probably his early twenties, slim and strong and absolutely silent. When he needs something, he points. He doesn’t waste his breath on words he knows we won’t understand. He mixes the cement on the ground, scooping, stirring, never stopping. I try to join him more than once with a second shovel, but I can manage barely half a dozen stirs before my arms start to burn. He goes on like this for hours, leaving little doubt as to which one of us is truly essential here.

Toward the end of the day, as several of us are on a water break, a man in probably his late thirties approaches us. His English is better than most; almost no one in Bouli speaks any English at all. And among the ten of us we have only a few dozen words of Creole.

“Not good,” he says. We are sitting and he is standing, stabbing his index finger in the air between us. “You should not be here.”

There is a long silence as we Americans eye each other warily. We all heard the same thing, but is it possible we misunderstood?

“You don’t want us here?” someone asks.

We can understand only some of his response, but his gestures, his expression, and the tone of his voice are perfectly clear.

In a mixture of English and Creole, we ask if it’s the clinic or the guest house or just us that is the problem. But with every failed exchange his anger creeps closer and closer to rage.

One at a time, we wander off back to work.

When I ask him later, Johnny suggests the man might have shown up looking for work. Johnny adds, with his usual diplomacy, that the man might have felt the work we were doing should have been done by someone like himself.

It’s a fair point. More than fair, in fact. In a country where around two thirds of the workforce is unemployed, who could blame a man for being annoyed at the sight of tourists fumbling through a job for free that he’s more qualified to do himself?

This is another part of the debate surrounding volunteer work and NGOs in developing countries like Haiti. For some observers, trips like ours create more problems than they solve. In addition to stressing fragile infrastructure and wasting scarce resources, these visits are said to deprive locals of much-needed jobs. A number of critics have contended that with the exception of trained medical personnel and others offering specialized skills, people who want to help should do so by sending checks to established aid groups, rather than coming in person.

After a day working side by side with an experienced Haitian crew, it’s hard for me to deny that my checks have done more good than my prowess with a shovel.

At around five o’clock, we break for the day. The floor is mostly done, as are several other projects we hadn’t anticipated. We’re dusty and dirty and sweaty and tired. My legs and arms are gray with cement. Nightfall comes at six, and we want to wash off in the river before dark.

As we collect our bags and water bottles, the Haitian crew keeps working; they will work until sundown.

Only later, as we’re eating dinner, do we learn just how much this crew has done today. What we saw for ourselves, it turns out, was only half of it. Not only did their day end after ours, it began long before we awoke.

Although the crew is from Bouli, they came here this morning from Boucan-Carré. The long trip we made the day before, they themselves made this very morning. Unlike us, however, they had no car to drive them half way to Sivol, no donkeys to take them from Sivol to Bouli. Their morning commute, around twelve miles, took them somewhere around five or six hours. Which they managed on foot, carrying their tools.

And then, without pausing, they proceeded to build a house.

§

In Bouli, without electricity, complete darkness came at six o’clock. We had only a handful of flashlights and candles by which to eat. After dinner there was rum. We brought three liters of Barbancourt, one for each night. When we left yesterday after finishing work on the guest house, not a drop remained to pack out. The drinking was largely a way to pass the time, to keep from going to bed the minute the sun went down. We were often tired enough that going to bed at six o’clock would have felt perfectly reasonable.

Last night, after our hike back to Boucan-Carré from Bouli, I fell asleep the moment my head hit the pillow. It was the first time that’s happened since we arrived in Haiti. And I slept soundly, waking up just once, at around 2:30 in the morning. I didn’t know what woke me. I went to the bathroom and then I got back into bed. I fell right back to sleep.

§

I wake up for good at 6:30. One of the other guys is already out on the veranda when I appear with my coffee. We exchange bleary “good mornings.” My head is still fuzzy with sleep, and when he asks if I felt my bed shake in the middle of the night, I at first think he’s trying to tell me about his dreams. It takes several more sips of coffee before I finally understand what he’s saying.

Johnny shows up a short while later. He confirms it: there was an earthquake very early this morning in the Dominican Republic, Haiti’s neighbor to the east. A 5.3. The quake reached us as only a minor tremor. Even at the epicenter, though, there was no significant damage, no casualties.

Nevertheless, it’s a troubling reminder of the 7.0 quake of January 12, 2010, which brought to this already fragile country a catastrophic disaster.

And experts say it could happen again.

Since our tremor this morning, a rumor has been circulating that there’s a sixty-five percent chance that another earthquake will strike Haiti this year. But even if one doesn’t strike this year, one is likely to in the near future. Some geologists, analyzing data from the 2010 quake, believe that only half of the fault line ruptured. That means the other half, the half even closer to Port-au-Prince, is still to come. This has provoked calls from some quarters for the government of Haiti to consider relocating its capital. At the very least, it’s another argument for developing other population centers. Port-au-Prince’s current burdens are more than it can bear. As things stand, it’s hard to imagine how the country could survive another. But it’s also hard to imagine where the funds for such a massive undertaking would come from.

§

Today, our last full day in Haiti, we take a trip to Saut D’Eau, a lush, fertile agricultural area on the perimeter of the Artibonite Valley. The fields here are the greenest we’ve seen: congo beans, bananas, potatoes, millet, and sorghum in abundance. And although there’s nothing resembling a forest, there are noticeably more trees.

Water is also more plentiful here. We see that for ourselves at the Saut D’Eau Parc Naturel waterfall, a small cascade with a series of pools at the end of a shaded path. Sitting there in the mist under a canopy of green, it feels good to be reminded of the island’s still considerable beauty.

From Saut D’Eau we go to Mirebalais and then on to the remote village of Cange in the Central Plateau. Between Péligre Dam and Cange, Route 3 winds along a narrow ledge carved into the mountain. A bare rock face presses up against us on one side; the other side is a precipitous drop to the waters of Lake Péligre, hundreds of feet below. In the narrow strips of land alongside the asphalt, little wider than the shoulders of an ordinary highway, are hundreds of tiny houses, some so close to the road I feel almost as if I could reach out the window and touch them. Many of the ones on the Lake Péligre side are so close to the edge they look as if they’re partly floating on air. An unsettling number of the houses have developed a backward lean. It looks as though a modest rain would be enough to wash them, and their inhabitants, straight into the abyss.

Until the late 1950s, Cange was located in the valley below, where Lake Péligre is now. But when the dam was built in 1956, the people of Cange lost their homes and their farmland to those unrealized dreams of tourism, large-scale agriculture, and universal electricity. This is where the displaced wound up. As recently as the mid-1980s, as Paul Farmer has written, the new Cange resembled a treeless refugee camp.

The alarming sight of all these houses tilted toward the precipice is part of what makes the sudden appearance of Dr. Farmer’s Zanmi Lasante medical complex so surprising. There is a bend in the highway, and where just a moment before there was nothing but huts and sky, there suddenly looms what looks like a dark gray fortress, slightly obscured by trees and thick stone walls.

Zanmi Lasante is the Haitian arm of Partners in Health. Its operation is centered here in Cange. Begun in 1985 as a small community clinic, the Zanmi Lasante hospital has grown in the years since into a vast sociomedical complex crawling up and down a series of switchbacks notched into the mountainside. The full-scale, one hundred-four bed hospital has two operating rooms, adult and pediatric inpatient wards, an infectious disease center, a women’s health clinic, a laboratory, a Red Cross blood bank, a dozen schools, and numerous dormitories for its predominantly Haitian staff.

On an average day, the Zanmi Lasante complex sees three hundred fifty patients. In 2011, PIH’s various clinics across Haiti—including the one in Boucan-Carré built with HOP—served 2.8 million patients. Nearly all of them receive treatment for free.

Like PIH’s massive new teaching hospital nearby in Mirebalais and the Haiti Outreach Program’s projects in Boucan-Carré and Bouli, Zanmi Lasante is the kind of undertaking that gives one a sense of hope for making real, lasting change in Haiti.

For his part, Johnny believes things are getting better, at least in Boucan-Carré. He thinks his neighbors and family feel the same way. And there are still more improvements to come. Johnny says the United Nations will soon be paving the road from Domond to Chambeau. That, like the arrival of electricity before it, will change Boucan-Carré in profound ways, connecting it to the rest of the region in a way it never has been before.

When I ask Johnny what else he might like to see done here, he says, “jobs.” He specifies agricultural jobs, including jobs planting trees. Experts in Haiti and in the international aid community agree that arresting the country’s most urgent environmental problems must begin with reforestation.

But Johnny would also like to see an orphanage here. He says one is desperately needed; there are countless vulnerable children living on the streets of Boucan-Carré and the surrounding area. Their already substantial numbers swelled following the earthquake; meanwhile, resources and infrastructure to support them has grown increasingly scarce.

Johnny himself has an adopted daughter. Her father died in the quake; her mother could not take care of her. She and Johnny’s other daughter go to school now in Cap Haitian, a mid-sized city on Haiti’s northern coast. The schools in Boucan-Carré are getting better, Johnny says, but they’re not yet good enough.

But while there’s adequate reason to feel optimistic about improvements in places like Boucan-Carré, optimism becomes more difficult to sustain the closer one gets to Port-au-Prince. Haiti’s capital is home to nearly half the country’s population and to the vast majority of those three thousand NGOs. Here, progress toward fixing some of Haiti’s more systemic problems has been harder to measure.

On Friday morning, the day after our trip to Cange, we return to the capital for our flight back to Tennessee.

As Route 3 carries us down from the mountains into the basin east of Port-au-Prince, we leave behind what little green there was to be had. Here in the Plaine du Cul de Sac, even much of the brown has washed away, exposing the bleached, bare rock that lies underneath. The landscape looks something like a post-apocalyptic film set. There are even several mysterious fires burning on the arid plain, the largest right at the northern edge of Trou Caïman lake. The smoke is thick and black, and whatever’s burning seems almost certainly toxic.

Once known as the breadbasket of Port-au-Prince, the plain is now a desert. Besides cacti, the only thing growing along the highway are low, desolate shrubs. As we pass, I struggle to imagine that any of this can be saved. On the surface, it appears the government has reached the same conclusion. The earth has been opened up for quarries. A fleet of dump trucks line up along the shoulder, awaiting their turn to load up on limestone and sand. This is how Port-au-Prince will be rebuilt, making use of what’s already been lost.

But can Port-au-Prince really be rebuilt? If so, there’s still a long way to go. Johnny and all the other young people I spoke with in Boucan-Carré want nothing to do with the city. They don’t like to go there; they certainly don’t want to live there.

Even if they did want to go to Port-au-Prince, it’s hard to imagine there being any room for them. From the moment we enter the city limits, there ceases to be any empty space. Everywhere we look, someone is already living, or at least trying to. The traffic is bumper to bumper. The people are shoulder to shoulder. They came in search of jobs and opportunity and a better quality of life—all things Port-au-Prince has been unable to provide.

Perhaps the country’s best hope is that places such as Boucan-Carré and Bouli and Cange can be made livable and accessible and sustainable, partly with the help of groups such as Partners in Health and the Haiti Outreach Program. Haiti’s future may very well be found in its past, in the countryside from which so many of Port-au-Prince’s current residents fled.

§

As we sit in Toussaint Louverture International Airport a short while later, waiting for the flight that will bring us first to Miami and then to Knoxville, I think about our first evening here. Sitting on the deck of the guest house in Port-au-Prince, we took turns explaining why we had come. The common motivation among us was that we wanted to help. It’s impossible to think of that now without also remembering the man we met in Bouli, desperate to tell us we didn’t belong here—that our presence was doing more harm than good.

Even now that the trip is over, I don’t know who is right. For the future, it may well be that my checks to groups such as PIH and HOP will do more good than my labor and my physical presence have done. But right or wrong, the one thing of which I’m certain is that I’m glad I came. Everyone around me seems to feel the same. There’s some knowledge that can be obtained only by experiencing for yourself, however briefly, what other people experience on a daily basis. Whether that means sifting sand and carrying water or having to hike a quarter mile to take a bath in a cold stream. In practical terms, this knowledge is what fuels projects like the ones the Haiti Outreach Program has undertaken here; it’s what creates sustained investment. While our labor lasted just a couple of days, the labor of the paid Haitian crews will go on for months and years.

For a while now I've made Haiti the main target of my charitable giving, but nothing can replace having actually been there. I know I will give more, and do more, and tell other people about the importance of the projects I’ve seen, than if I had never gone. Beyond that, the connections I made with Johnny and with the students in Boucan-Carré and the people of Bouli are a valuable reminder that this is not and never will be a republic of NGOs. It is these young Haitians who are shaping their country’s future.

But even though it’s the Haitian people who must rebuild Haiti, I’m optimistic that there will remain a place for partnership. The value of working together is more than just material. If the last eight years have taught me anything, it’s that we have as much to gain from Haiti as we have to give.

christopherhebert